New study finds strong link between anti-Israel and antisemitic beliefs, and increased likelihood of antisemitic beliefs amongst British Muslims

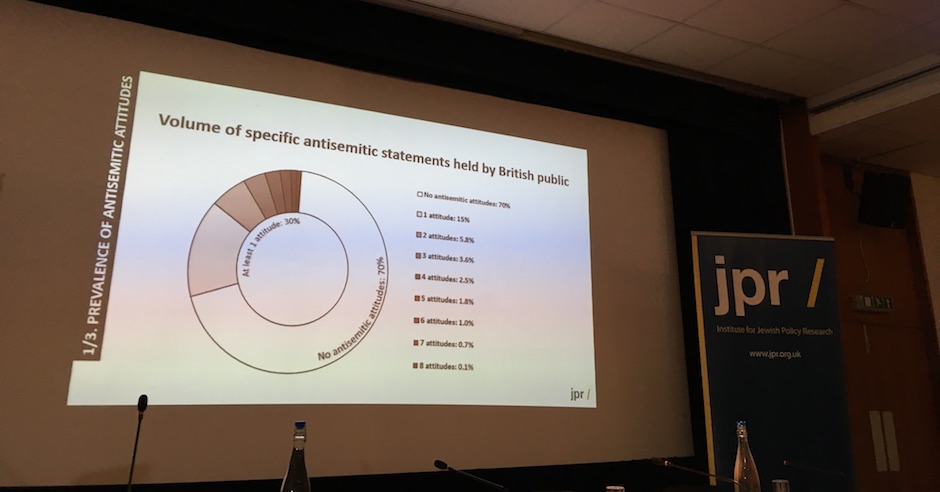

A new study by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research (JPR) has confirmed that approximately one third of British people hold at least one antisemitic prejudice. The study, authored by Dr Daniel Staetsky, corroborates Campaign Against Antisemitism’s own research, whilst also venturing into new areas, examining the relationship between antisemitism and anti-Israel beliefs, and providing further detail on antisemitism amongst the far-left, far-right and Muslims.

The report is very detailed, and it is clear that considerable effort and expense has been devoted to providing it as a freely-available resource for those interested in the study of antisemitism in Britain.

Adopting a very similar methodology to our Antisemitism Barometer polling conducted with YouGov, JPR commissioned Ipsos MORI to show a sample of British people a selection of statements about Jews: some positive, and others of a nature that Jews typically recognise as antisemitic. 30% of British people hold at least one antisemitic view according to the JPR research, whereas our YouGov polling put the figure at 36%. The small difference is only just outside the margin of error, and is likely to be accounted for by differences in the antisemitic statements and the definition of antisemitism used.

The JPR report then goes beyond our research, asking respondents whether they agree with a number of “anti-Israel” statements in order to measure the correlation between negative beliefs about Israel and negative beliefs about Jews. Under the terminology adopted in the JPR report, only the statements about Jews per se were classified as antisemitic, although some of the statements about Israel would also be classified as antisemitic under the International Definition of Antisemitism. For example, respondents who agreed with the statement that “Israel exploits Holocaust victimhood for its own purposes” or that “Israel has too much control over global affairs” are extremely likely to be expressing beliefs that engage the International Definition of Antisemitism, but the JPR study simply classifies these beliefs as anti-Israel, not antisemitic.

This part of the study does confirm what many have long suspected: that there is a very strong link between negative beliefs about the Jewish state and negative beliefs about Jewish people: 43% of people who agree with at least one anti-Israel statement also agree with at least one anti-Jewish statement. For example, those with anti-Israel views were especially likely to agree with statements that “Jews think they are better than other people” and “The interests of Jews in Britain are very different from the interests of the rest of the population”. Most disturbingly, 49% of those with strong anti-Israel attitudes were found to agree with the statement “Jews exploit Holocaust victimhood for their own purposes”.

Delving further still, JPR sought to identify the extent to which antisemitism flourished amongst particular political and religious groups, finding that antisemitism was much more likely to be found on the far-right and amongst Muslims (especially amongst religious Muslims) than amongst the British population in general. Indeed JPR found that British Muslims were approximately twice as likely as the rest of the British population to hold antisemitic beliefs.

The study’s findings with regard to antisemitism on the far-left may prove controversial. Unlike Muslims and members of the far-right, survey respondents describing their politics as far-left appeared no more likely than members of the general population to agree with negative statements about Jews. However, the study found the same link between negative statements about Israel and negative statements about Jews among people on the far-left that it did among members of every other religious and political group. In other words, it found that a person who holds multiple negative views about Israel is likely to hold negative views about Jews, regardless of whether that person sees him- or herself as belonging to the left, the right, or the centre.

Moreover, the study found people on the far left to be much more likely to agree with negative statements about Israel – so when we consider the manner in which some antisemitic beliefs were classified in the study as being anti-Israel rather than antisemitic, it seems likely that the far-left in fact does have a disproportionate antisemitism problem when judged using the International Definition of Antisemitism instead of the JPR criteria.

JPR also sought to gauge support for violence against Jews, finding that 14% of British people consider “violence against Jews in defence of one’s political or religious beliefs and values” to often, sometimes or rarely be justified. 71% said that it was never justified and 15% said that they did not know or preferred not to say. However the study also showed that British people held similar views about the legitimacy of using violence against a range of targets, ranging from banks to European Union institutions.

In one respect in particular, the JPR study raised more questions than answers: if 30% of respondents agreed with antisemitic statements (as defined by JPR) and only 4% of respondents within that 30% self-defined as far-left, far-right or Muslim, what do the remaining 26% of British people who hold antisemitic beliefs have in common? Discovering the common denominator that unites that unaffiliated, casual grouping of antisemites remains as elusive as ever.

Finally, JPR’s results should be interpreted in the light of the methodology used. For example, when JPR asked whether respondents viewed Jews favourably, 5.4% of respondents said that they viewed Jews unfavourably, 46.8% were neutral, and 38.8% said that they viewed Jews favourably, with the remainder saying that they did not know. However, when JPR asked the question without the option of expressing neutrality, the percentage of respondents expressing unfavourable attitudes towards Jews more than doubled, suggesting that some people with unfavourable views towards Jews may have preferred to express neutrality to hide their true views, and only express their real feelings about Jews when they are not given an opportunity to express neutrality. Since JPR did allow respondents to express neutrality in all but one of its questions, it is reasonable to assume that more respondents would have expressed antisemitic views had they not been given the option of answering neutrally. In other words, it is possible that JPR’s results would have been much worse had they forced respondents to make choices.